Not long ago, we were all talking about what tearing down statues meant. An article by Boaventura de Souza Santos argued that those objects, usually “visited more intentionally by pigeons than by humans”, have become battlegrounds because of how they represent “unsettled accounts and unredressed depredations and injustices”. Their images, as part of our cultural heritage, can “resurrect, create and preserve certain narratives”, writes Lucas Lixinski in his latest book. Statues serve as bridges of time, erected between past and present.

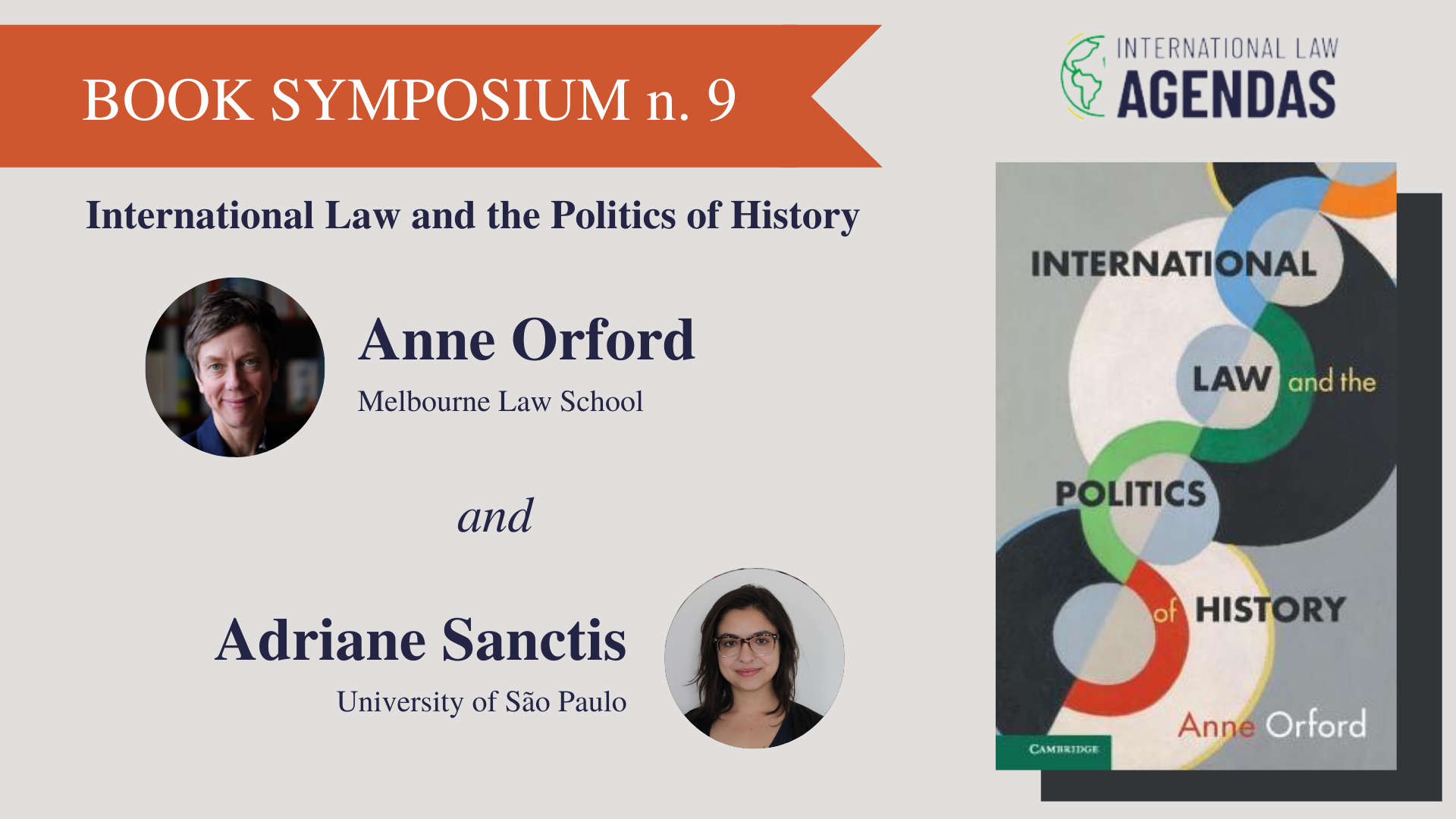

Anne Orford’s new book, ‘International law and the politics of history’, deals with that same connection. She focuses on a particular encounter between lawyers who have appropriated history in the last few decades, and historians who disagree with that approach and call for a more contextual treatment of the past. Orford also intervenes in that encounter and argues that certain claims (by contextual historians or those who adopted their takes on legal history) create room for a post-realist formalism in international law, under the pretence of neutral, scientific, and empirical grounds. With the statues debate in mind, I suggest that we could rephrase the main argument of the book as the following: as lawyers, we may have deviated from the reality —so material and visible in statues— that representing the past shapes the present.

If you have ever engaged with legal history, Orford’s book will make you question the most basic choices of your work from the first page to the last. You start by having doubts about how implicated you are in the note Orford leaves at the Introduction: “If your professional commitment and goal is to produce scholarship that complies with historical protocols rather than to intervene in the present work of international law [,] […] [t]hose historians can leave now with my blessing. This book is not for or about you.” After you pass this first test, prepare for an intensive session of deconstructive reflection about your deepest affective connections.

Orford’s starting point is the “turn to history”, a phenomenon that begins in the 1990s and reinvents the way international lawyers resort to the past. This was far from the first time lawyers turned to historical approaches. Textbooks have always abounded in practices and readings, short versions of genealogies and teleologies. The innovation was lawyers mobilized history for critique and “as a means of professionally engaging with the past”, mostly “with ‘presentist’ concerns”. The past was central in critical arguments over very concrete questions such as the US expansionism (and the legacy of imperialism) and changes in legal interpretation after September 11.

That turn to history came to be perceived as problematic by some historians, who saw ‘improper contextualization’, ‘anachronism’, ‘presentism’ in the ways the lawyers have articulated the past. These charges resonated with some lawyers, who in response took to empirical methodology imported from contextual historiography to an alleged neutrality in mobilizing the past in legal arguments (the “turn to method”). Orford sees this as a new trend of formalism in international law, which acts as a kind of fact and method “laundering” through history.

“Statues look a lot like the past, which is why, whenever they are called into question, we turn to historians,” writes Santos. That may be so when they are mostly noticed by pigeons, but less so when statues come under attack. Then, it is what they represent which is at stake, and might be to some extent independent of what archives can tell us. Historians still have a role, of course, but it is hardly surprising that their word is not dispositive of the controversy. I see that same realization in how Orford takes issue with historians who defend a ‘right way’ to do history when it comes to international law.

Yet Orford’s book is not a criticism to the entire discipline or profession of historiography. Orford does not mean, in her words, to make a “call for the barricades” or to build a “wall to separate law and history”, but to reflect on how we think and construe their relation. The problem she identifies is rather the tendency to consider historians’ accounts of the past as objective.

‘International law and the politics of history’ heavily criticises contextual thinking, arguments in favour of “more archival work”, and scrutinizes recent historiographical works aimed at showing the legal reality of past times. Those criticisms notwithstanding, I read Orford’s book not as a call for losing all that baggage history brings (with all its internal debates and disagreements), but as a call for seeing it is fundamentally entrenched with political disputes, from which the characteristics that makes it identifiable also emerge. The book did not make me less drawn to Arlette Farge’s passionate account of how “talkative documents can be” or less taken by the ‘allure of the archives’. Yet the reader is compelled to think and rethink about what Orford underscores as the actual problem and main target of the book: the pretence to “reveal” the truth about legal history and thus to ignore the political responsibility to construe it through legal arguments.

Anne Orford’s book is an excellent reminder of how tools of knowledge and political responsibility may help us out of the very human creations that are disciplinary straitjackets. In Anne Orford’s words, “if your ambition is that somehow your study of the past can, and perhaps even should, inform an engagement with and potential transformation of the work that an object called ‘international law’ or people called ‘international lawyers’ are doing in the present, this book is written for you.” The book is so much as unsettling as it is valuable, a warning against hegemonic narratives about how things got this way, the ‘statues’ of who we are and what things should become.

-

Adriane Sanctis de Brito é diretora e pesquisadora pós-doutoral do Centro de Análise da Liberdade e do Autoritarismo (LAUT). É Sylff Fellow da Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research e já atuou como professora contratada do Instituto de Relações Internacionais da Universidade de São Paulo. Foi pesquisadora bolsista no Instituto Erik Castrén da Universidade de Helsinque, no Instituto Max Planck de Luxemburgo e no Programa Laureate de Direito Internacional na Universidade de Melbourne. É graduada, mestre em direito internacional e doutora em teoria do direito pela Universidade de São Paulo - USP.