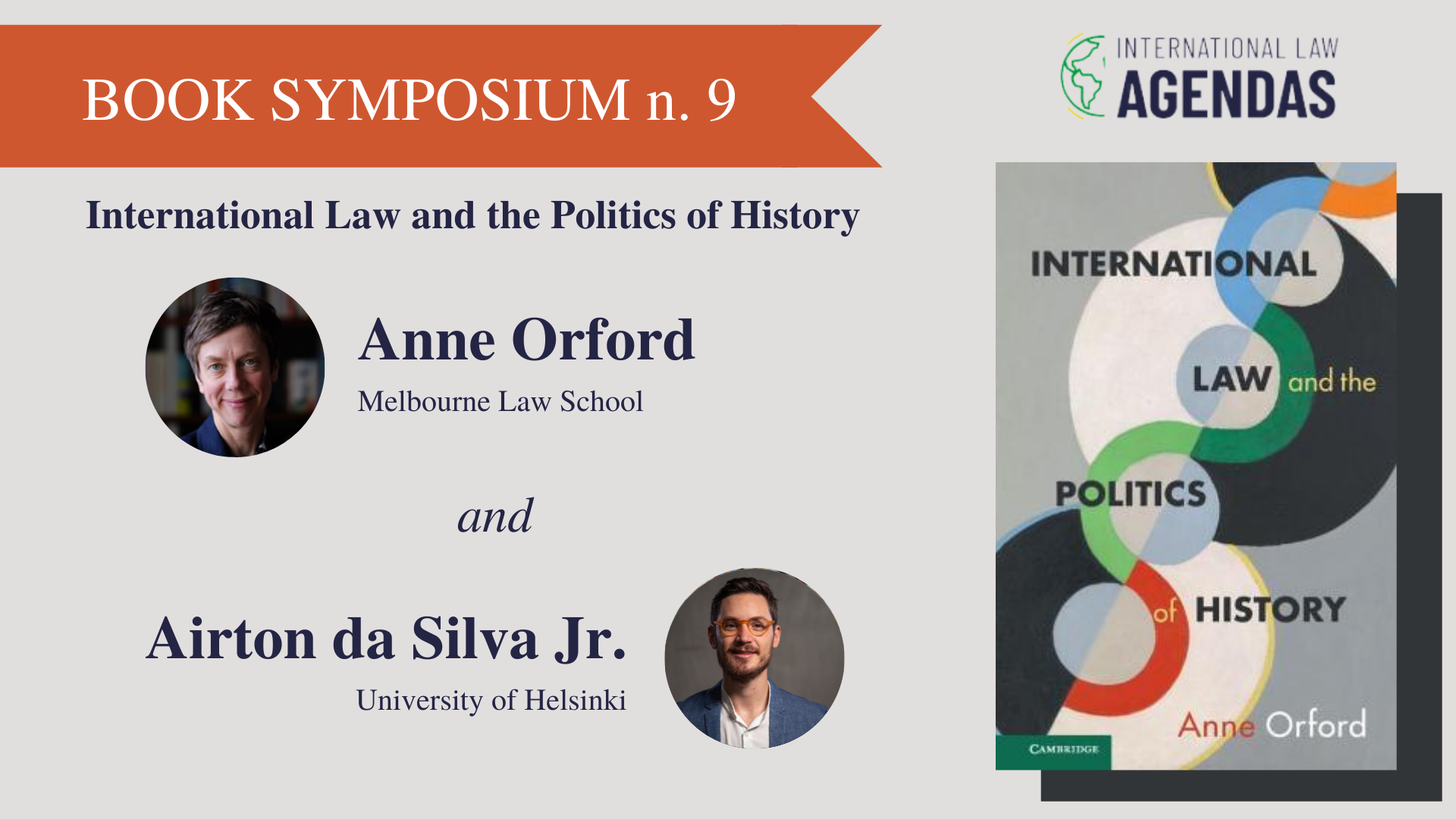

The question above is one of the many that arises while reading the thought-provoking ‘International Law and the Politics of History’ by one of the leading scholars of international law, Anne Orford. That is what good books do: they make us think and question, in this case, about the relationship – or frictions – between international law and history, and even, between international law and its own past.

Since the discipline of international law experienced a turn to history, witnessing a growing interest in the history of international law, there has been an intense debate about the boundaries of these two disciplines and their methodologies to engage with the past. In this exchange of arguments on how international lawyers should properly work with past materials, Orford in ‘International Law and the Politics of History’, reacting to the criticisms of professional historians and legal historians regarding the historical methods required to produce consistent and verifiable narratives, claims that “empiricist history offers a new grounding for formalism” since these allegedly scientific methods disguise partial and partisan accounts of international law. The main problem, according to her, is that these ostensibly neutral historical narratives accounting for the ‘true’ past of international law unavoidably become part of political struggles in the present, within and beyond the academic realm. The line of argumentation follows a realist assumption: if the present law is ‘made, not found’, then to assert what past legal texts mean would also involve decisions and choices that historical methods cannot prevent.

On behalf of the coherence of these claims, some concessions had to be made regarding historiography. Her criticism targets particularly the contextualist approach proposed by the so-called Cambridge School. Despite being just one of the approaches that can be applied in a historical enterprise, it ended up representing all of historiography. In any manner, throughout the book, she censures ‘empiricist historians’ – a designation that seems redundant as history should be primarily based on evidence – for failing to deliver on their promise to offer a value-free, impartial and neutral account of the past of international law. However, the discipline of history has been much less self-confident about the limits of historical methods than Orford describes it. Uncertainties regarding the work of historians and their ability to faithful reconstruct a past reality ut sic have long been at the center of historiographic debates, even before the linguistic turn and the radical skepticism of Hayden White. There are unsolved aporias regarding the craft of history, such as the tension between past and present in the encounter of an interpret situated in the present and a reality that is already gone, accessed through the remaining traces. In chapter 6, Orford explores this tension, charging legal history works with presentism for employing current concepts. It is worth stressing that the present is always the starting point, and it is impossible to free oneself from the pre-comprehensions of the present. As once stated by Benedetto Croce, any history is contemporary history. In such a manner, historical narratives are indeed fragile. And yet, despite this atmosphere of uncertainty, all scholars aiming to narrate the past with a consistent and verifiable narrative still share and uphold a minimum set of historiographical standards, because they constitute epistemological conditions of the historical knowledge and distinguish history from any other engagement with the past.

After all, to whom does the past of international law belong? Is the past the monopoly of historians? Certainly not. The past is at everyone’s disposal whether to use or to comprehend it. While a generic use of the past might ask at least some coherence to function as a persuasive argument in a legal dispute, the latter requires the commitment with some minor rules of historiographical labor. It should be stressed, then, there is nothing wrong with mining the past in support of a position or offering an overtly anachronistic in a legal argument, as long as it works. An international lawyer can arbitrarily use the past, the historian shall not. In fact, Orford brilliantly makes that point in chapter 5, illustrating the many ways that international lawyers make use of past material.

The comparison between the judge and the historian, to which the author also resorted, exemplifies the differences of each appeal to the past. As clarified by Pietro Costa, even though both the work of the judge and of the historian operate in a hermeneutic character, their purposes are neatly distinct. The judge primarily aims to solve a conflict, while finding out the truth would only be an instrument to reach it. Also, the judge selects the facts that matter, that may have legal consequences, filtering precise facts according to a particular legal system. The historian, on the other hand, has a cognitive purpose. The aim is to understand the past on its own terms. Thus, the historian has a commitment to this reality that passed. Even if the beliefs or pre-comprehension from the present play a minimum role in the dialogue between the past and present, these judgements do not constitute the main purpose of the historical enterprise. Otherwise, as pointed by António Manuel Hespanha, the dialogue between past and present would turn into a monologue of the present, where the past’s autonomy would be deprived.

And that is probably the most conflicting point of the disciplinary debate since Orford calls scholars for an open commitment with the present-day of international law and its struggles for justice. As she asserts, international law, remaining largely customary, must resort to the past to assert its rules, turning the past into a site of dispute. The histories of international law presented by professional historians are employed by lawyers to intervene in contemporary debates. However, as she proclaims, since historical methods cannot guarantee objectivity, then accounts of the past of international law should assume their partial character, instead of hiding behind the methodology.

It is worth underlining that historical methods and the different approaches that a historian may use to undertake an investigation about the past are what make historical knowledge possible. Nevertheless, they cannot protect us from bias, nor from support for political causes. Methods help us to construct subjective narratives and yet verifiable. It is possible to scrutinize the validity of its results. Still, historical narratives always represent perspectives about the past, like a narrow beam of light in the dark. In this sense, there can be as many narratives as historical approaches focusing on different aspects of an object situated in the past. That is why history can be perceived ‘as completion and correction’ as Orford rightly indicates. After all, there are still histories of the French Revolution being written. There is no definitive history.

Orford’s ‘International Law and the Politics of History’ shakes the disciplinary boundaries of international law and history, provoking us to question the intersections between them. I would conclude that the constructive effects from her gripping positions are the need to pluralize historical approaches, to diversify the objects and actors studied in the past, especially giving voice to silenced voices often excluded from the histories of international law. Scholarly debates shall continue, fortunately, to improve awareness about what we are doing. Yet, if the gate to the past is not guarded by any historical method, history’s gate better be.