Every book is two books, no? The book that the author has written, and the book that his readers have read. And the book launch or a symposium like this brings the two books into a kind of conversation. My book now reads differently to me. Is it, for example, as Maddy Chiam has recently suggested, “a manifesto”[1]? If I had thought of this before the book came out I might have renamed it. I certainly think of it differently now. And this symposium has in its multiple ways shifted my thinking about the book or the book after the book. I have certainly been struck by the generous, open-hearted tone of the four essays, each, in its own way, not just responding to the book but writing in its spirit. It filled me with great pleasure to read these careful, attentive reviews. A little bit of me, then, wants to just leave them there, unresponded to. Especially because there is so little I can add and nothing much I want to disagree with. But that’s enough of diffidence and what Don De Lillo called “these deeply preliminary remarks”, what do I think of the reviews of my book, you ask?[2]

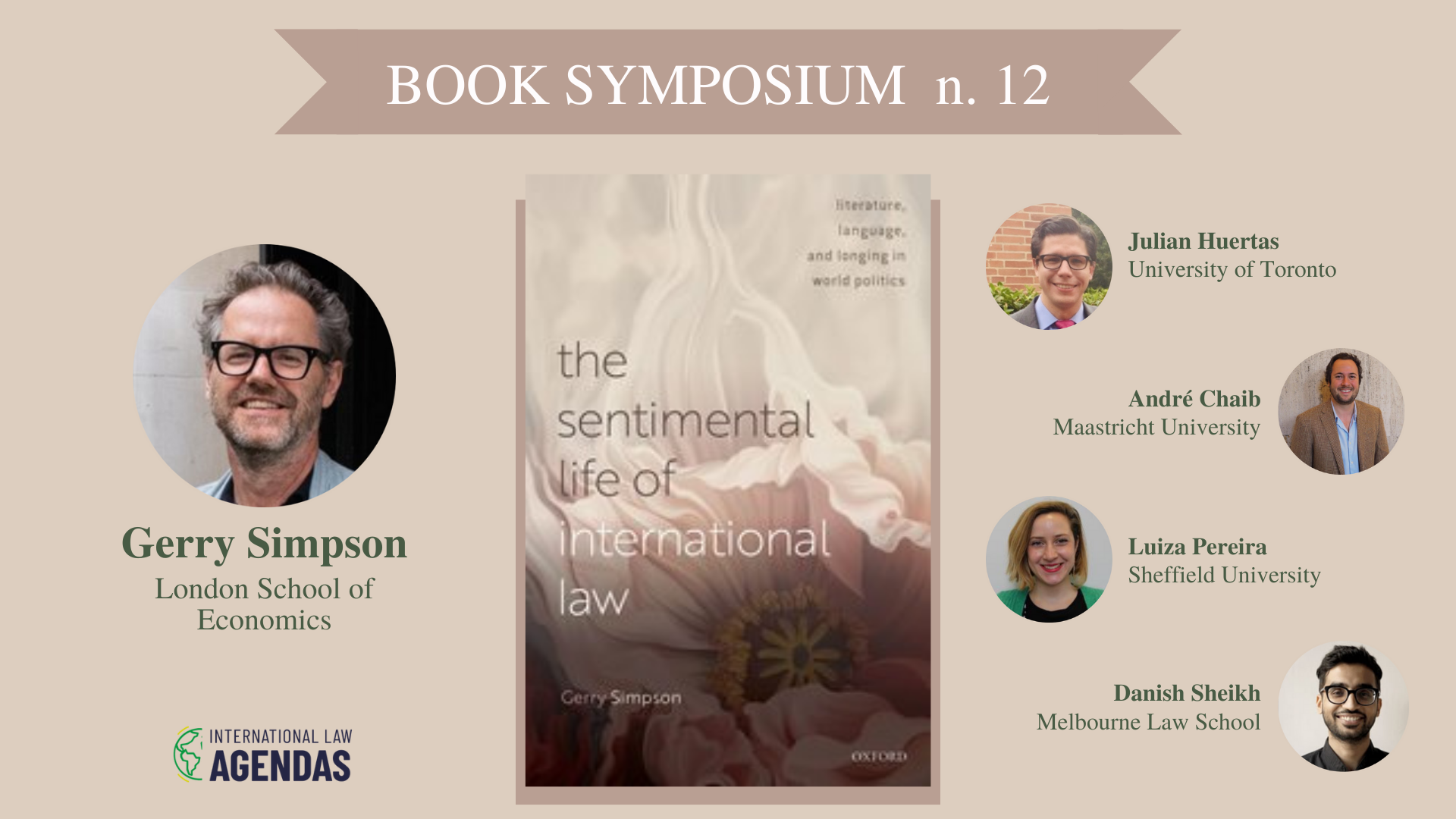

Let’s start with Julian Huertas, who places my book alongside the case of that brave journalist, Jineth Bedoya, and the recurrent horrors perpetrated on people in Colombia and other parts of Central America. This, of course, is very tricky terrain for my book. Some of the book seems to be pointing to a mismatch, or dissonance, between the language of international law and those human experiences that it seeks to express or accommodate or speak to. This is, at least, partly, the “bathos” point. Of course, as soon as I put it these terms, it comes out all bathetic. Is that what my book is about?

Julian is fine with the bathos but worries that, as a response to Bedoya’s pain (or the solemnity of legal proceeding) ironic or blasphemous laughter might be too risky or ineffectual or quietist. The stakes are too high “in transitional contexts” and so this ironic laughter should serve as a kind of background signage to remind us of the limitations of humanitarian law: “But only that”, and certainly not as part of a programme for political action, as he says and implies. I wonder though, and this is off the top of my head, if we don’t need to apply irony to the political projects themselves? After all, there are dangers on both sides of the rocks. The enemy is real and must be defeated but the seriousness, the bloody-mindedness, the vitality of the struggle can so easily give way to a repetition of the authoritarian violence and centralised power. I want irony at the heart of power not on its satirical margins.

But Julian gives a fine example of the kind of hard-earned sentimentality that in the book I seem to like when he talks about the court in the Bedoya case charting its course between dry dispassion and excess melodrama. And he widens this thought into a broader point about what he calls “artisanal forms of international law”. I have no idea what these might be, but I wholly support them.

Andres Nunes Chaib reads my book alongside Pessoa, Clarice Lispector and others. And he redescribes it as an attempt to practice or write about an international law we do not tend to discuss or even think of as international law in the first (or last) place. I especially appreciated his way of capturing this idea of me showing how “international legal life is just as imbued with the sentimental and aesthetic dispositions we identify in any other acts of our mundane day-to-day lives” as well as his own various literary juxtapositions. He also picks up on a common reservation about the book (though he couches the latter in a very discreet, diplomatic admonishment, the language of the friendly critic, one might say), namely that its interlocutors are largely drawn from a North American-European literary tradition. He recommends (indeed performs on) a broader canvas of these literary traditions.

In a similar vein, Luíza Leão Pereira’s review discusses the book as a kind of view from Hampstead. As she points out, I spend a lot of time anticipating the possibility that the book will appear to have been written from a position of privilege while working hard to counteract that thought (by emphasising huge reservoirs of self-awareness: there is, after all, a whole section on the idea of “luxuriating”). But there’s no getting away from it, this is the kind of book that could only have been written by a version of me (elite tenure, moneyed advantage, a certain kind of education, sheer good fortune). I suppose I was trying to spend some of that capital on a loss-making experiment. Quite a lot of people have said to me they felt a kind of kinship in my description of the agonies of the early career scholar, so I suppose I am trying to remember a more precarious moment.

It has been pointed out to me, by an old friend, that the book defies critique by turning the critic into one more character in the book. And Danish Sheikh’s essay confronts this problem head on when he asks – in sparkling prose – “how to describe the texture of this book without reducing it to the kind of unsatisfactory, affectless simmer against which it ostensibly writes”. That’s funny. And just as good, he re-characterises the book as a Dictionary of International Law. That turns me into a Samuel Johnson figure, which I’ll take (absent the endless maladies). In the end, Danish reads my Sentimental Life against Ann Carson reading against Hegel in Merry Christmas From Hegel, as an inhabiting of mood or atmosphere, a cultivation of sensibility.

To return again to Luiza: she picks up an awkward transition from scepticism to idealism in the way the book is organised. The first set of chapters – which she likes – are offered in a mode of ironic distance where sentimentality hovers between tears and what she delightfully calls “giddy hope”. But after that the whole thing goes off the rails and becomes “saccharine”. My lawful friendships are dubious (Henry Kissinger in an incidental role in one, Khrushchev betraying the Castro revolution in another). Meanwhile gardening, to return to an earlier point, is available only to those with real estate (literal and/or metaphorical). She describes these chapters as “wistful” which made me want to immediately write another book called The Wistful Life of International Law. Like all the best reviews, this one made me consider the book in a quite different light, made me want to keep writing, keep thinking, keep moving in the hope of not arriving.

________________

[1] Madelaine Chiam, Comments, Sentimental Life of International Law, Book Launch Event, Jindal Law School, 26th May, 2022

[2] Don DeLillo, “The Art of Fiction No. 135” 128 Paris Review, Fall, 1993.