It is not uncommon for professionals in any field of law to understand or perceive themselves as indispensable or to view their work as infused with a higher level of importance given the subject with which they deal or the types of things they do. International lawyers are no different. Nevertheless, a great deal is lost when these same professionals write, discuss, or describe their work without realizing some of the non-formal aspects of what they do. This has often been the case because international law is a universe where scholarship and practice are powerfully intertwined. In this sense, a book like The Sentimental Life of International Law by Gerry Simpson should be very warmly received. Professor Simpson offers us a formidable reassessment of the very elements, often unspoken, that compose the distinct character of international law and lawyers and how we relate to international legal life. In between the intellectual exercises and the practical strategies in which international lawyers engage, one often forgets about the sentimental aspect of the lives of international lawyers and international law.

The book draws on various examples of international law’s operations to illustrate the different forms through which international lawyers manifest sentiments (be they sentimental excess, sentimental simplicity, solipsism, or de-politicisation – pp. 43-47). Such examples – the work of scholars, lawyers in international courts, etc. – also reflect specific dispositions of lawyers that we often purposefully leave aside. We leave them aside not only because as international lawyers we have become detached from sentiment, but also because we have assumed an almost undisputed aesthetic position in our professional lives. Although Simpson focuses on the sentimental part of international law’s life, there is no denying that his work navigates the aesthetic dimension of international law and lawyers’ lives and operations. And yet the aesthetic character of international legal life does not only pertain to its sublime, beautiful, or ugly character, nor with personal taste about liking it or not. Instead, it relates to how we understand the field – and those inside the field – should be seen or perceived. Aesthetics concerns the way international law and lawyers should appear to the world. In this sense, telling the sentimental life of international law is inevitably associated with re-enacting the aesthetic forms of international legal life. These are some of the consequences of articulating ‘sentimental-literary ways of thinking or practices’ (p. 113) in international law or thinking of international law as a ‘cultural project’, a language, a set of symbols’ (p. 148).

The sentimental manifestations Simpson describes, and the ironic or cynical international lawyers (p. 87) can be easily identified in the different political spaces where they operate. For example, in international organizations, where international lawyers constantly interact with other professionals, it is easy to identify those instances where ‘solemnity and chaos’ generate the ironic laughter of lawyers (p. 63) as a reaction to the frequent impotence of their institutions to solve practical problems. One can think, for example, of the various international conferences (e.g. the International Labour Conference and the various UNFCC Conferences of Parties), the meetings of the Human Rights Council, or the various meetings taking place in all sorts of departments where lawyers, economists, political scientists, and politicians sketch out plans to simultaneously solve the world’s problems (unemployment, poverty, human rights violations) and give meaning to their work. In many of these operations, we see international lawyers trying to articulate a language of formalism with sentiment, not in ways to serve as ‘mawkishness’ (p. 52) but rather to reinforce the meaning of their presence in those settings.

Trying to expand the umbrella of legality, as Machado de Assis once said is the primary formal, and sentimental, but most importantly, aesthetic disposition of lawyers in international organizations, trying to articulate the various limits of international law in world politics. It is a constant exercise of the ‘doubleness’ to which Simpson refers when discussing the ‘critical faith’ of international lawyers when they feel as if they ‘can’t go on,’ and yet ‘must go on’ (p. 73).

Tal é a nossa concepção da legalidade; um guarda-chuva escasso, que, não dando para cobrir a todas as pessoas, apenas pode cobrir as nossas; noutros termos, um pau de dois bicos.

Machado de Assis, Notas Semanais, 16 June 1878, II (‘Such is our conception of legality; a meagre umbrella, which, not being able to cover all the people, can only cover our own; in other words, a two-pronged stick.’ Our translation)

And although international lawyers, like Álvaro de Campos – one of Fernando Pessoa’s many heteronyms – may hold in their chests more humanities than Christ, or elaborate more philosophies than Kant, or even ‘conquer’ the world before getting out of bed they are just continuously operating simultaneously on the global stage and in the garrets.

I’ve held more humanities against my hypothetical breast than Christ.

I’ve secretly invented philosophies such as Kant never wrote.

But I am, and perhaps will always be, the man in the garret,

Even though I don’t live in one.

I’ll always be the one who wasn’t born for that;

I’ll always be merely the one who had qualities;

I’ll always be the one who waited for a door to open in a wall without doors

And sang the song of the Infinite in a chicken coop

And heard the voice of God in a covered well.

Believe in me? No, not in anything.

Let Nature pour over my seething head

Its sun, its rain, and the wind that finds my hair,

And let the rest come if it will or must, or let it not come.

Cardiac slaves of the stars,

We conquered the whole world before getting out of bed,

But we woke up and it’s hazy,

We got up and it’s alien,

We went outside and it’s the entire earth

Plus the solar system and the Milky Way and the Indefinite.

Fernando Pessoa, Tobacco Shop, Excerpt, Translation from Portuguese by Richard Zenith, in Fernando Pessoa & Co, Grove Atlantic, 1998.

Indeed, it is common to view the work of international lawyers as a rather tedious one. Like with other types of legal work, one may even question why it is really necessary (reminding us of David Graeber’s critique of corporate lawyers, for instance, in his Bullshit Jobs). However, when one talks about international law as this almost personalized entity, we notice that in our professional field the feeling of usefulness or uselessness is not so foreign. For example, there is a constant critique of the political nature of the work done – as if any other type of legal work were not imbued with and in politics – and the constant challenge it faces from the designs of power. As a reaction to this critique, international lawyers often recur to the formal aspects of their work: international legal rules exist and ought to be interpreted according to well-accepted forms of interpreting them. This resort to formalism should be valid for international courts and states and international organizations when operating in what we call the international. Whether we speak of challenges to existence, validity, correctness, or whatever else one might think of international law, those who work within the field admit its inevitable presence in their (ours?) everyday life.

Unlike what one might believe, Simpson’s book is not interdisciplinary (and here, I take the cue from pp. 113-114, where he indeed hopes his book will not be labelled as such). Instead, it is a different type of intervention that seeks to engage with the very aspects of international law and lawyering we experience but often refuse to discuss. These are experiences that inform, influence, and determine the conditions under which the life of international law operates. Talking about sentiments, or better yet, the dispositions that international law presents and international lawyers as agents have – if this dichotomy is possible – provides us with a different and much welcome form of looking at how international legal life happens. To do that, Simpson’s engagement with international law beyond the formal aspects of the work offers a breath of fresh air into a literature otherwise dominated by jargon and vocabulary unfamiliar (to say the least) to those outside the field. Bridging aspects of literary life (p, 118), imagination, and everyday life practices, such as gardening, to rethink how international law’s experience can – and should – be understood differently is a necessary exercise in both scholarship and practice. Yet as a matter of critique, it would have been perhaps good to see more mentions of authors belonging to literary and artistic traditions other than those of Europe and the Anglo-Saxon world; not because they would offer different experiences and modes to see the world of sentiments, but just because they might.

The book is written in a way that both simplifies understanding core aspects of international legal life (without shying away from indicating its main complexities) and humanizes international law, making sense of how it affects those most directly involved with its operations. The plea for an engagement with sentiments in international law reminds one of the eventual absurdities of our professional lives as international lawyers. It makes us think that, as again Fernando Pessoa said in his Tobacco Shop, ‘there are no more metaphysics than chocolates.’ The book’s writing style is unequivocally distinct – and perhaps purposefully so – from most types of interventions in international legal scholarship (it even offers the reader a hint of the author’s humour, when after a long footnote on p. 34 where he describes an experience he had in the United Nations headquarters, in New York, he suggests to the reader a ‘reference’ on long footnotes). It puts words where they should be and not in between the lines, as Clarice Lispector would advise.

Já que há de se escrever, que ao menos não esmaguem as palavras nas entrelinhas

Clarice Lispector, Jornal do Brasil, 7 June 1969 (‘If you have to write, at least don’t squash the words between the lines.’ Our translation)

Although the book centres on the experiences of international lawyers and international law, it does not claim any particular place for the discipline in the universe of law. On the contrary, it helps us realize the opposite: perhaps the very experiences we have in international legal life are just as imbued with the sentimental and aesthetic dispositions we identify in any other acts of our mundane day-to-day lives.

-

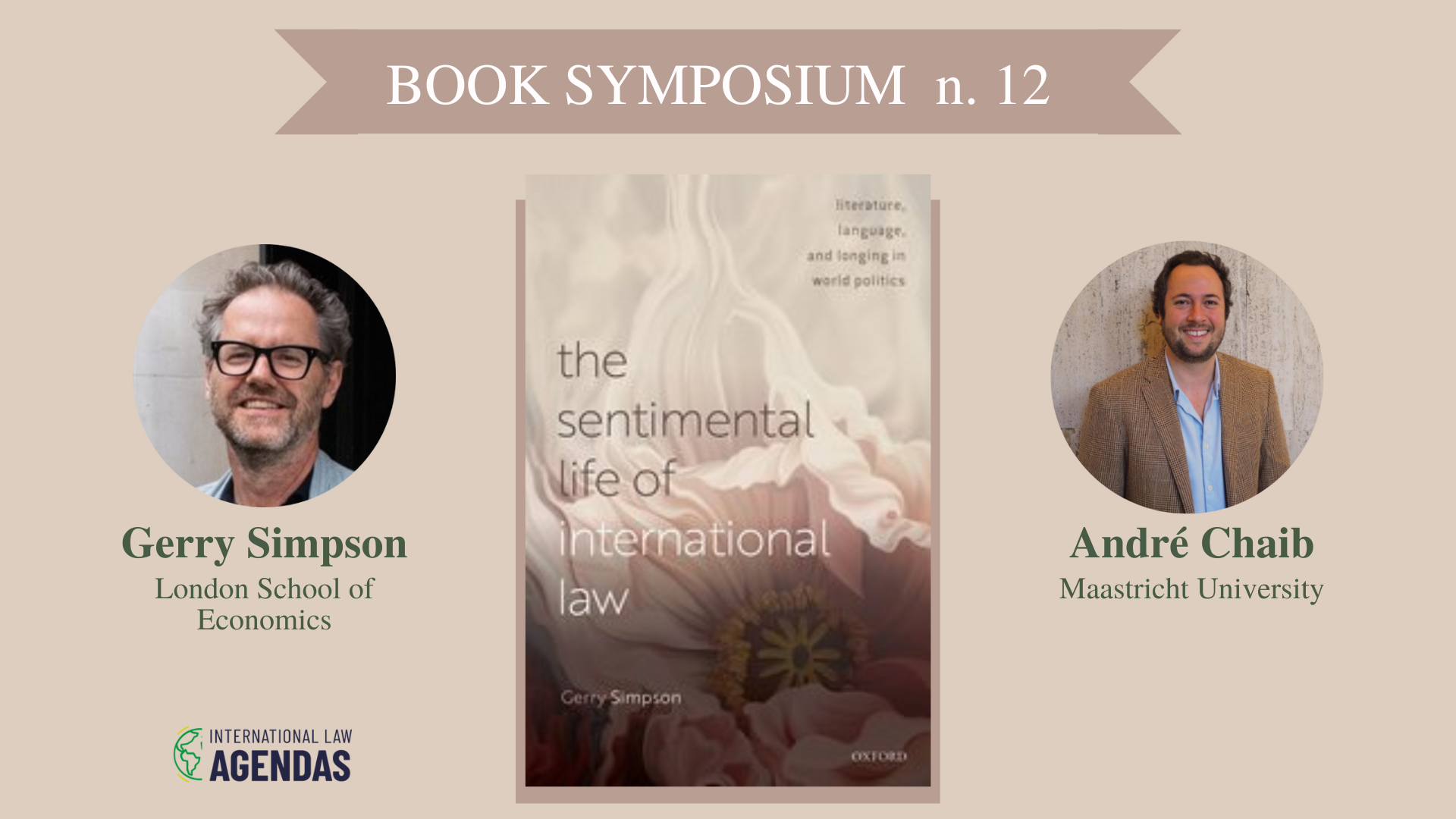

Dr André Nunes Chaib is Assistant Professor for Globalization and Law at the Faculty of Law, Maastricht University.