The objective of this blog post is to explore the potential impact of investment screening mechanisms (ISMs) on the transfer of technology to developing countries and their effects on tech transfer regulation. ISMs are a recent development, primarily studied by research institutes and projects in high-income countries such as Europe and the US (e.g. CELIS Institute in Europe, the PRISM Project in Princeton and The Beauty Contests which involves Princeton University, University of Trento and the University of Oslo). However, the focus here is to examine ISMs from the perspective of emerging markets and developing economies, analysing their impact and suitability for these contexts.

In summary, the text (a) analyses ISMs as a high-income country phenomenon with potential impacts on emerging markets and developing economies; (b) evaluates their main drivers calling attention to a notable one, i.e. technology leadership; and (c) discusses the ways under which ISMs could hinder technology transfer to emerging economies and how they could bring about shifts in international technology transfer regulations. It concludes by shedding light on the need for a balanced approach that harmonizes national security concerns and collaborative global efforts in aspects relating to technology.

ISMs as a high-income country phenomenon

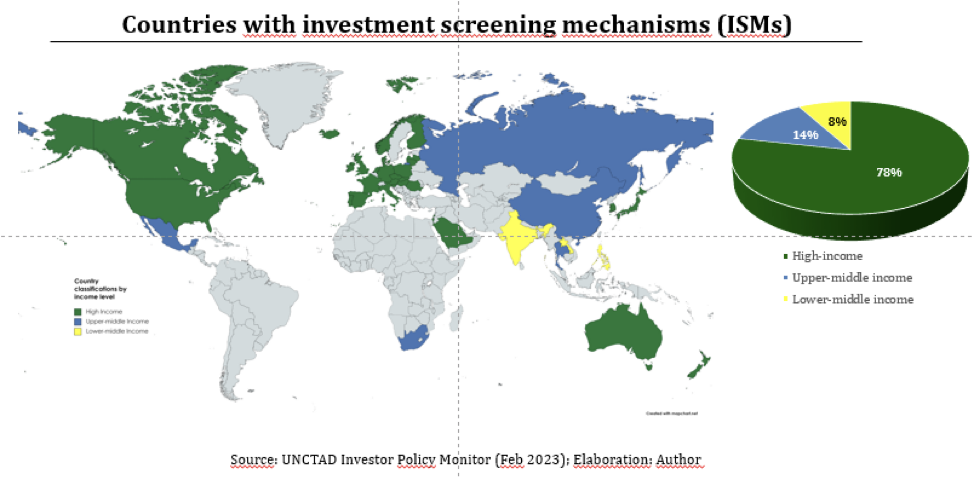

The map below shows that 78% of the existing inbound ISMs are adopted by high-income countries, meaning that they have formal instruments in place to control foreign investment entering in their countries.

After the global economic and financial crisis in 2008, and with the expansion of outward foreign direct investment from developing countries, more developed countries began to introduce dedicated regimes for inbound investments screening mechanisms. Starting from 2016, countries have introduced a significant number of amendments to existing investment screening regulations, mostly seeking to expand their scope based on national security grounds.

As it is possible to see in the map above, this is a trend in high-income countries not in emerging markets and developing economies.

Conversations are also underway within the US and the EU regarding the implementation of an outbound system, which would allow these countries to regulate investments made by their own companies in other nations. On August 9, 2023, President Biden issued an executive order directing the Treasury Department to establish a program to oversee a new instrument to review outbound investments in national critical sectors, including quantum technology, artificial intelligence and semiconductors.

Drivers of ISMs

Various drivers contribute to the implementation of ISMs and the increasing emphasis on national security considerations such as geopolitical tensions between US, allies, and China; and now between Western countries and Russia; perceived vulnerabilities in the production chains which was amplified by the impact of COVID-19 among others.

In this post, however, I would like to call attention to one specific driver: technology.

Advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, Internet of Things, biomanufacturing, quantum computing, microelectronics and dual purposes technologies are among the major national security concerns within the framework of ISMs.

These advanced technologies tied with the Fourth Industrial Revolution will reshape production and consumption patterns. The countries that lead in these technologies with not only enjoy economic advantages but, more importantly, they will have power.

When analysing the countries’ motivations for implementing inbound ISMs, it is possible to observe common concerns. They are preoccupied with being technology leaders and in preventing technology leakage that could facilitate the development of foreign technologies, particularly from China.

Many countries have included critical or advanced technologies under the scope of ISMs and linked them to national security concerns.

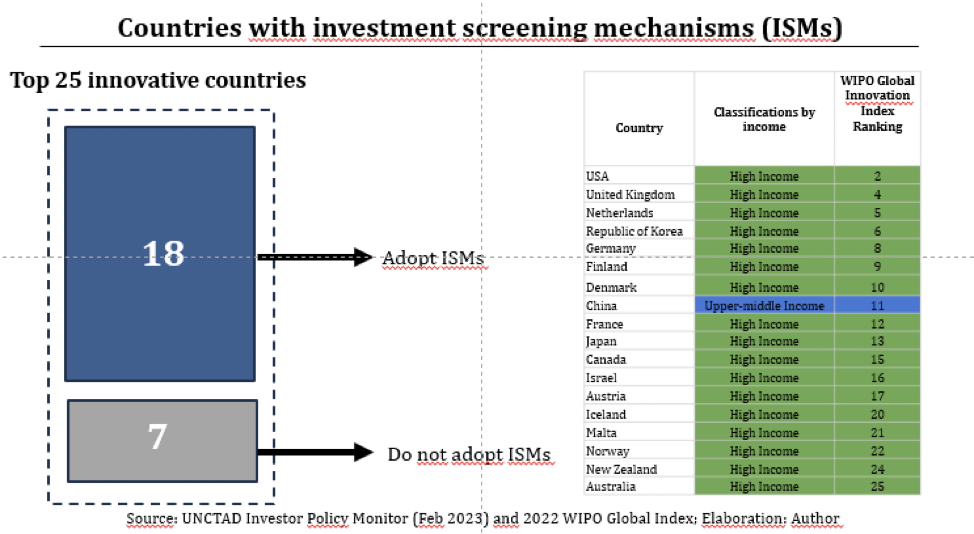

From this perspective, ISMs seem to have been used as an industrial policy for governments to establish themselves in particular technological sectors and to protect domestic technology. This seems to be evidenced by the fact that 17 of the 25 most innovative countries in the world according to the WIPO innovation index adopt ISM, as can be seen below:

How emerging markets and developing economies can be affected by ISMs and by the fact that high technologies are among the sectors affected by such instruments?

InApril this year, the IMF has published a study mentioning that “Fragmenting Foreign Direct Investment Hits Emerging Economies Hardest”

In this context, ISMs could in theory adversely affect technology transfer to emerging economies in at least 2 ways:

- By restricting investments made by emerging-market multinational corporations. These companies have significantly expanded in the last two decades and have been seen with concern by certain developed countries as many of them are state-controlled or have some influence from their home governments. ISMs have also been introduced to some extent as a response to expansion of outward foreign direct investment from developing countries.

- In the case of potential outbound ISMs, they could restrict FDI in developing countries particularly considering that it is not clear if they would be included in current “friendshoring” measures or if they are considered “like-minded” countries in view of their trade relations with China. Outbound investment screening mechanisms are already a reality.

All this could have negative impacts on technology transfer to low- and middle- income countries and on their innovation and productivity levels. The ultimate result could be widening the technological divide between developed and developing countries.

What about the potential effects of ISMs on the regulation of technology transfer?

The proliferation of ISMs along with friend-shoring could have the potential to bring about changing trends in the regulation relating to international technology transfer and technology protection.

Traditionally, countries have protected their technology through national IP laws, patent laws.

With the intensification of trade among countries, the industrialists of the most

technically developed countries launched the idea of international protection of patents. Then, we had the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property

Later on, the TRIPS Agreement was a solution to make all countries, including developing countries, adopt minimum standards of IP protection.

Afterwards, there was a trend, on the part of developed countries, to enter into trade and investment agreements with developing countries with TRIPS-plus provisions, which increased their standards of IP protection and restricted domestic technology transfer requirements.

Until recently, this movement by developed countries was carried out

to some extent through consensus-based and negotiated mechanisms, as both the TRIPS Agreement and trade and investment agreements presupposed negotiations.

With the advent of investment screening mechanisms, countries seem to be transitioning from consensual regulation to unilateral measures with extraterritorial scope to protect their domestic technologies and keep them within the boundaries of their national territories or the territories of like-minded countries. For instance, mitigation measures adopted in 2021 by the US Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States involved prohibiting or limiting the transfer or sharing of certain intellectual property, trade secrets, or technical information to foreign investors. Additionally, considerations of national security have added a new layer to the regulation of technology.”

It is particularly worrying how the concept of national security has been applied to transactions involving technological sectors.

But don’t high technology sectors involve certain risks and threats that justify their analysis based on national security grounds?

Technology does come with risks and threats such as privacy and data security; cybersecurity risks; disruption of critical infrastructure; cyber espionage; military applications.

Nevertheless, these risks could be better addressed by framing them in more technical aspects rather than political ones.

Additionally, there are alternative approaches to dealing with these risks instead of relying solely on a unilateral system of FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) review based on national security considerations.

The Copenhagen School of Security Studies has an interesting definition of national security: security is a narrative/a speech act built by the state to convince an audience and justify exceptional measures. Its logic is based on “drama, urgency and exception.”

In Brazil, for instance, in from the 60s to the 80’s and in many other Latin American countries which suffered with dictatorship, we lived with a doctrine of national security that only served to supress individual rights and basic rule of law guarantees.

This logic of suppression of rule of law guarantees seem to be present in current ISMs as, by analysing their functioning, we can see lack of transparency and motivation in their decision-making process.

Some conclusions and thoughts

Advanced technologies bring unique challenges that require collaborative efforts, not unilateral measures. Issues such as data protection, privacy, and cyber threats cannot be resolved by the state alone. They are more effectively addressed with common frameworks and coordinated responses.

International cooperation is a better option to tackle these challenges more effectively. Regulating advanced technology also requires a multi-stakeholder approach, involving not only governments, but the private sector, civil society, and experts. This is the opposite of national security mechanisms with their secret and opaque decision-making.

Emerging markets and developing economies have better chances in an integrated world rather than in a fragmented one.

Advanced technologies pose intricate challenges that demand a balance between national security and collaboration. While ISMs may appear necessary to protect critical technologies, their potential to impede technology transfer to developing economies warrants careful consideration. A holistic approach that emphasizes international cooperation, transparency, and shared decision-making is necessary to ensure a harmonious technological landscape that benefits all nations.

-

Natália de Lima Figueiredo é professora Adjunta no curso de Direito da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Unifesp). Doutora em Direito Internacional pela Universidade de Maastricht e Universidade de São Paulo (dupla titulação). Membra da Rede Latino-americana de Direito Econômico Internacional.