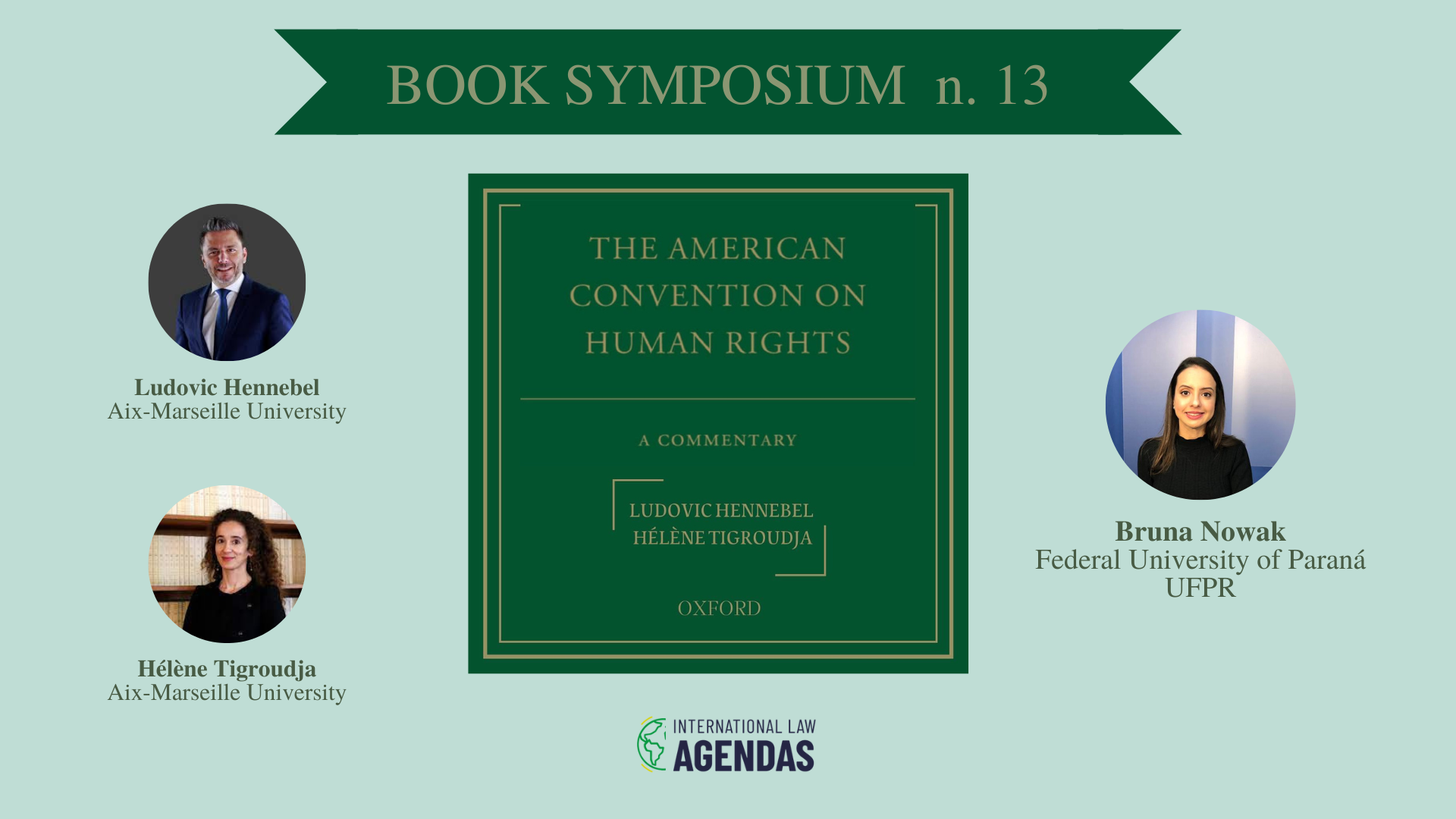

Hennebel and Tigroudja’s “The American Convention on Human Rights: A Commentary” is, I believe, the most complete analysis of the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR or Convention) ever published in the English language. I congratulate the authors for the extraordinary work. My purpose is to (humbly) read this commentary in light of the jurisprudence on reparations determined by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR or Court), since they are one of the most emblematic features of the Inter-American System of Human Rights (IASHR or System).

Following the article-by-article structure of the book, I will divide my review into two moments. Firstly, I will present some reflections about the material content of reparations, focusing on pecuniary compensation and guarantees of non-repetition (article 63). Next, I will make observations about the procedural aspects of the monitoring compliance with judgments’ phase (articles 65 and 68). The book covers all the important facets of reparations. However, as it will be argued, it could be stronger in detailing the difficulties to enforce these remedies.

When one talks about reparations in the IASHR, one automatically refers to article 63.1 of the ACHR, which provides that, in case of a human rights violation, the Court shall rule “that the consequences of the measure or situation that constituted the breach of such rights or freedoms be remedies and that fair compensation be paid to the injured party”. The authors are very intentional in connecting this article with Public International Law’s institutions: the law of state responsibility (having the International Law Commission’s Draft Articles as the main reference) and customary international law. This is not a common approach among Latin American scholars, who usually consider the System “hermetically” due to its specificities. Hennebel and Tigroudja’s move is a good one because it goes back to the commonalities that underpin the human rights systems, which can also be helpful for comparative purposes. Regarding the victims of the human rights violations, it is interesting to notice that article 63.1 refers to “injured party”, a frequent terminology in the law of state responsibility. For the authors, the injured parties are considered according to a “needs-based approach”. I would also say that the Court’s case-law is developing sophisticated parameters about intersectionality – which can be understood as multiple vulnerabilities that make the victims more susceptible to violations. For example, in the Case of the Employees of the Fireworks Factory of Santo Antônio de Jesus and their families v. Brazil (2020), the Court concluded that the victims “were immersed in patterns of structural and intersectional discrimination” (§ 197), since they were afro-descendant women and girls in a situation of structural poverty.

The book also points out that there is no provision in the ACHR that specifies the consequences of a breach of the Convention. This gives the Court a wide room of possibilities to establish the due remedies. This “full reparation” approach makes the IASHR sui generis – especially when compared to the European System. In that respect, throughout the entire book, there are constant mentions to the European Court of Human Rights, since it served as an inspiration to the IASHR. I will come back to this point below.

Specifically about the types of reparations, the authors dedicated many pages to pecuniary damages (loss suffered and loss of profit) and the correspondent reparations (e.g. the elements taken into account by the Court to decide the compensation to be paid by the state). I had never read such a complete analysis on this topic. However, in my point of view, this is not the main feature of the Court’s remedies. In fact, even though in pretty much all the sentences the Court orders compensation in the form of thousands of dollars, what distinguishes the IASHR are the other forms of reparations. At the same time, one can point out that revealing this methodology can put the Court on the spotlight also regarding compensation, so the other international courts – which focus primarily on this type of reparation – can learn from the IACtHR.

Indeed, the authors affirm that the Court has developed “a case law that is unparalleled on non-pecuniary measures” (p. 1323). These measures are very specific in relation to the damage caused and the victim’s profile (for instance, the intersectional factors). They also have a symbolic nature, which is so characteristic of the IASHR. About that, I quote a peculiar decision delivered by the Court. In the Case of Tavares Pereira et al. v. Brazil (2021), the IACtHR issued – pending the judgment on the merits – provisional measures to guarantee the preservation of a monument that already exists and carries out the name of Mr. Tavares Pereira. This monument will probably be included as a measure of satisfaction in the upcoming sentence.

One of the most controversial measures of reparation concerns the duty to investigate, prosecute and, if applicable, punish the persons responsible for the human rights violations. I noticed that the book does not explore how difficult it can be for the state to fulfill this obligation, especially because of the statute of limitations – and/or the controversial amnesty laws in our region. However, the authors comment about the Case of Fontevecchia and D’Amico v. Argentina (2011), in which the IACtHR ordered to state to cease the effects of a judicial decision. At first, the Argentine Supreme Court refused to do so, but the domestic tribunal changed its decision afterwards.

As someone who worked on the implementation of the IASHR’s decisions in Brazil, I believe that the guarantees of non-repetition constitute the cornerstone of the Court’s jurisprudence on reparation. The book does not explore the Court’s evolving jurisprudence in this regard. Even though the guarantees of non-repetition are unique, the authors mention that these measures are in accordance with the law of state responsibility. This perspective caught up my attention because it seeks to root the Court’s extravagancy in International Law’s classic foundations.

One of the most remarkable examples of guarantees of non-repetition was ordered by the Court in the Case of the Employees of the Fireworks Factory. In operative paragraph 18, the Court determined that the state shall design and execute a socio-economic development program to facilitate the insertion of those working in the manufacture of fireworks into other labor markets and to enable the creation of economic alternatives in the municipality of Santo Antônio de Jesus. The Court defined some elements that must be included in the program and requested the state to provide annual progressive reports on its implementation. This is a public policy – and the Court has been determining this type of measure pretty frequently. It is yet to be seen how the Court will evaluate the enforcement of this obligation by Brazil. Will indicators be defined? Does the Court, as a judicial organ, have the technical expertise to supervise the execution of domestic public policies?

These questionings lead me to the second moment of my commentaries. Procedurally speaking, the ACHR does not provide an article about the monitoring with compliance of judgments. It is the Court that decides how to regulate this stage of the proceedings. Article 68 stipulates the state’s duty to comply with the judgment (inter partes obligation), and the Court incorporated the monitoring role into its judicial functions. It is article 69 of the IACtHR’s Rules of Procedure that indicates how the Court exercises this competence – and it has been doing so quite creatively. The authors’ analysis on this matter is very complete – I do not know any other work about this subject as detailed as this book.

When commenting about article 65 of the Convention, the authors stress that the OAS General Assembly does not have the power to supervise the Court’s judgments, nor to sanction the state. They add that “notwithstanding the activism of the Court on the matter, the lack of a political pillar remains one of the main weaknesses of the inter-American System”. I tend to disagree with this statement. The IASHR does not work according to the same logic of the European’s Committee of Ministers. I believe the Court should sharpen its supervisory tools by exploring more than the adversarial procedure of requesting reports from the parties of a case – mainly because the content of the reparations has evolved overtime.

The authors also highlight that the number of cases in the stage of monitoring compliance is considerably increasing each year. Regarding Brazil, until 2010, there were only five judgments. As of 2016, the Court has delivered a new judgment every year – with two in 2018, none in 2019, and two in 2022 (the second one to be published in the following weeks). The reparations determined against Brazil – as well as all the other states – are mostly classified by the Court as “partial implementation” and “pending implementation” in comparison to “total implementation”. The power of shaming that could be exercised by the OAS General Assembly would not be sufficient to change this reality.

Time is also a relevant element. The book states that “the requirement for closing a case is the full execution of all the measures” (p. 1409). In Brazil, none of the ten judgments have reached this status [1]. The authors mention the cases about enforced disappearance and extrajudicial executions as examples that take very long to be finalized. I would add the cases that involve guarantees of non-repetition in the form of public policies. In addition, there is a tendency to consider that compensation may be implemented more quickly – and this is repeated in the literature. I agree with the authors that “the financial aspects of reparations can also be very complex” (p. 1383). In Brazil, for instance, in the cases of inheritance, a judicial lawsuit will be necessary to enable the payment of the indemnity to the relatives of the deceased victim. As one can imagine, it takes a lot of time.

When talking about the obligation to comply with the Court’s judgments, the authors cite an article elaborated by two Brazilian scholars about resistance to the IACtHR’s decisions by supreme national courts. There is a vast academic production on this topic, due to the lack of exercise of conventionality control by the domestic tribunals. I would like to point out that more should be explored about the Executive branch’s resistance. I agree with the observation that “subsidiarity plays very little role in the inter-American law” (p. 1383), since the IACtHR leaves little discretion for the State to decide how to implement the reparations. This feature stands out even more when compared to the European System.

In sum, the authors study on reparations is very dense and full of references to the Court’s jurisprudence. The book is also systematized according to a “chain of ideas” structure, which enables cross-references among the Convention’s articles. But I would wish to see some aspects strengthened from the perspective of the practical experience working at the Executive sphere of a state that struggles to implement the IACtHR’s (and also the IACHR) decisions. Hennebel and Tigroudja’s book is a wonderful start and shows us how much more work is to be done to make this system live up to its promises.

Response by Ludovic Hennebel and Hélène Tigroudja

____________

[1] The Court has delivered eleven judgments against Brazil. However, in the Case of Nogueira de Carvalho et al. v. Brazil (2009), the State was not held internationally responsible for the alleged human rights violations, so no reparations were established.

-

Lawyer. Masters Degree in Human Rights and Democracy (Federal University of Paraná, Brazil). Member of the Study Group on International Systems of Human Rights of the Federal University of Paraná.