As François Ost asserts in Dire le Droit, Faire la Justice, law is logos, discourse, so there is a hermeneutical endeavor in defining the law, which is something to be worked on every day (une oeuvre herméneutique, un travail toujours recommence). The construction of international law is an ongoing project, where historic, cultural, and sociological factors exert influence over the perception of juridical concepts and institutes (Paulo Borba Casella, Fundamentos do Direito Internacional Pós-Moderno), comprising the interpretation of the evolution, formation and function of the sources of international law. However, doctrine and practice are still generally silent on the inclusion of non-Western legal traditions when considering history, structure and process of international law (even though there are already relevant manifestations in international law scholarship, see, for example, Anthea Roberts, Is International law International?; B. S. Chimni, The Past, Present and Future of International Law: A Critical Third World Approach). Therefore, voices such as Imogen Saunders’s are absolutely necessary for an inclusive and critical redefinition of international law.

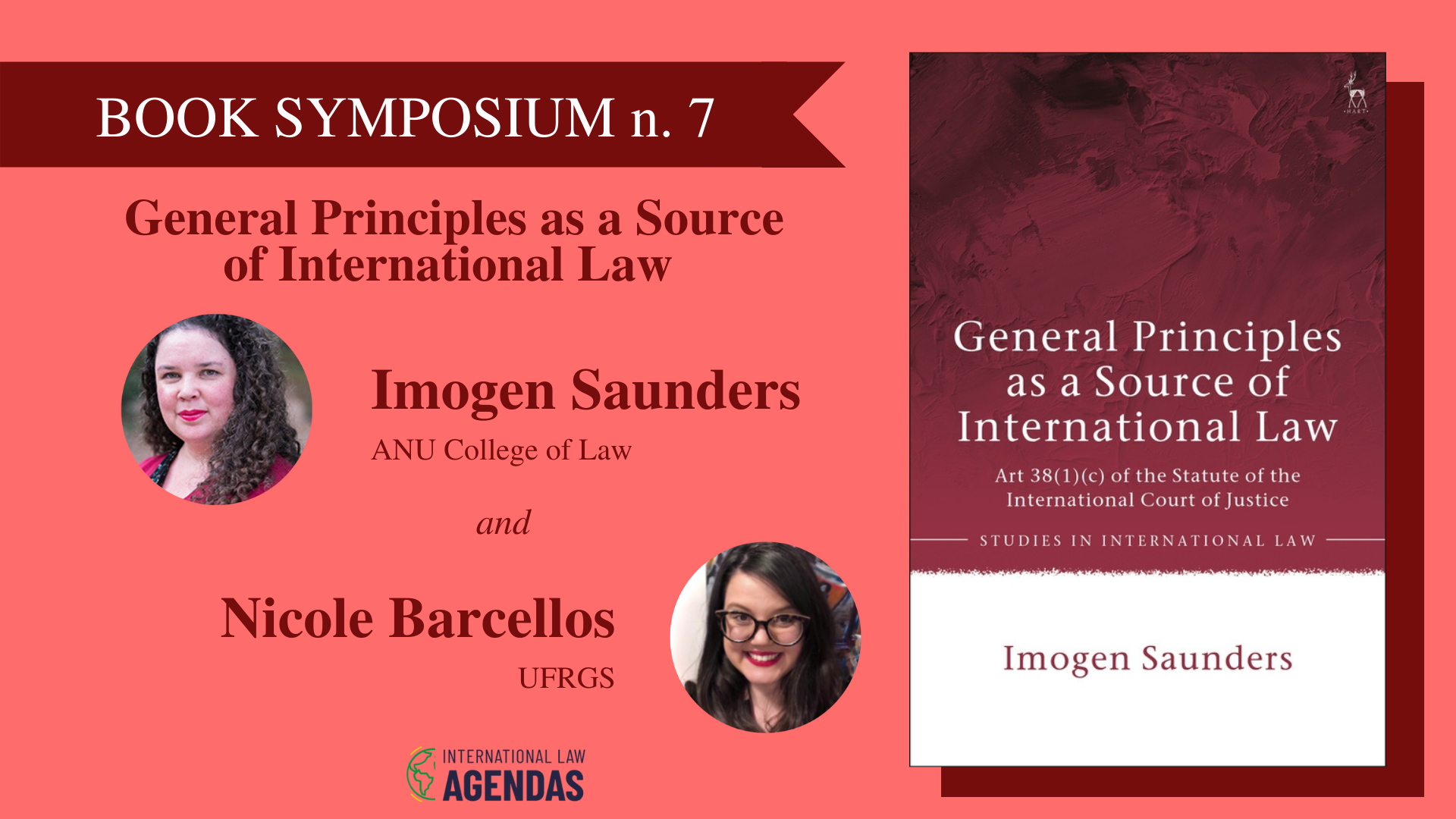

Imogen Saunders’s new book, General Principles as a Source of International Law, is a meaningful contribution to understanding this complex and frequently misinterpreted source of international law. The author conducts a study that takes into account the diversity and heterogeneity of legal systems and encompasses a contemporary view of its, proposing a method for the identification of genuinely Global General Principles. Notably, Saunders’s analysis considers non-Western and non-traditional legal systems, which are less commonly approached in the practice and theory of international law (chthonic, religious, and Asian legal systems).

General principles are included as a source of international law in Article 38, 1, (c) of the Statute of International Court of Justice. Even though this is far from being a new provision, many issues remain unclear, as expressed by Saunders in two provocative questions at the beginning of the book: “But what are they? And how do you find one?”. The book then clarifies concepts and dispels myths through an original framework of analysis, acknowledging General Principles through the lenses of function, type, methodology and jurisprudential legitimacy.

The author presents a broad collection of theories and opinions on the concept and extension of General Principles, emphasizing the many conflicting approaches to this topic. In effect, the subject has always been controversial within the practice of international courts and international law doctrine. These controversies commonly refer to whether General Principles are principles of international law per se or principles of national law, whether they are expressed by natural law or positivism, and the fundamental characterization of “civilized nations” (Antônio Augusto Cançado Trindade, Princípios de Direito Internacional Contemporâneo).

Considering that international legal ideas must have concreteness (Martii Koskenniemi, International Law in the World of Ideas), the system of international law is not abstract nor absolute, and the analysis proposed by Saunders encompasses both aspects. Starting with a historical approach of the General Principles and its implications, the book evolves to a comprehensive investigation on the practice of international courts regarding the consideration of Article 38, 1, (c), specially, but not limited to, the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The scrutiny of Article 38, 1, (c) and its development within the scope of international and regional courts brings interesting conclusions, which are paramount to the critical approach of the General Principles proposed in the final chapters of the book. I would like to highlight some enlightening considerations of the book that I believe to be instrumental to the construction of a contemporary and clear understanding of General Principles as source of international law.

Saunders shows that even though the PCIJ referred to a variety of General Principles in selected cases, and these cases are still attributed by doctrine as support for General Principles, these references defined a general rule or used a language that could refer to custom as well. Vague and amorphous statements contributed to an initial lack of clarity in this source of international law, because even though PCIJ refers to principles, they are not contextualized as General Principles until commentators did so. Later, within the scope of the ICJ, General Principles are expressly mentioned, but they are sometimes conflated with customary law, with rare discussions about jurisprudential legitimacy, adding a new layer of confusion and complexity to the topic. Nevertheless, there is a coherent treatment of this source by the ICJ. With the investigation on development of General Principles in other international or regional courts, Imogen Saunders points out to an interesting and contemporary issue: judicial cross-fertilisation. The activities of different courts involved in the judicial globalization are examples of a diversified process of interaction, in which judges observe and promote a dialogue between courts to respond to the challenges of the globalized world, taking their conceptions of General Principles throughout different tribunals (see Antônio Augusto Cançado Trindade, La Coexistencia y el Diálogo entre los Tribunales Internacionales; Anne-Marie Slaughter, Judicial Globalization).

The author demonstrates that General Principles are a binding source of international law, separated from conventional or customary law, with the accepted function of filling eventual gaps uncovered by specific norms in international law and solve the problem of non liquet (see, H. Lauterpracht, Some Observations on the Prohibition of Non Liquet and the Completeness of Legal Order; D. Anzilotti, Cours de Droit International). But they are not limited to that. General principles include procedural or substantive norms, abstract or generalized principles, and specific rules, in general. They are deduced by a comparative methodology (sometimes rather limited), and exist despite differences between legal systems, because of their inherent value (even though their jurisprudential legitimacy is mostly positivist, they recognize elements of content driven reason). This methodology brings into attention which systems are to be compared, considering that the development of international law has traditionally expressed European values and premises (see Antony Anghie, Finding the Peripheries: Sovereignty and Colonialism in Nineteenth-Century International Law). In this regard, Saunders states that comparative methodology is traditionally focused in national legal systems but should also comprise non-state legal systems, such as Chthonic and Religious. In doing so, the author proposes a recognition of multiple identities and heterogeneity, a desirable aspect of a critical approach to international law.

Lastly, the author considers a contemporary use of General Principles as a source of law, in light of the latest international developments. New areas of international law often do not involve state-to-state interaction, considering that States are not, and have not been for a long time, the sole subjects of international law. Saunders argues that General Principles have the potential to address new problems of international law, a theme I believe calls for further reflections (and could itself result in a whole book!).

Saunders’ book is an important contribution to contemporary international law scholarship, as it echoes critical theories that seek to revisit international law concepts and foundational assumptions which permeate international legal order, by looking at them from peripherical perspectives. In critical perspective, the author applies her theory exploring non-Western and non-traditional legal systems, such as the chthonic, religious, and Asian systems, demonstrating that there is a greater and growing understanding of the need to discuss models of law outside the traditional bounds that classically make up public international law (Imogen Saunders, General Principles as a Source of International Law).

For a global south perspective, this means that the author’s original methodology for the identification of General Principles also implicates in the recognition of values emanating from systems in this part of the world, responding to the need for democratization of the sources of international law and taking into account the rich diversity of cultures and legal traditions involved. International law is an instrument of power, and it can legitimize the subjugation of non-Western peoples (see Antony Anghie, Finding the Peripheries: Sovereignty and Colonialism in Nineteenth-Century International Law; B. S. Chimni, The Past, Present and Future of International Law: A Critical Third World Approach). Therefore, the construction of truly global international law must necessarily encompass a contextually-responsive and ethically-accountable understanding of its sources, such as General Principles, based on recognition and inclusion. And that’s exactly what Saunders does in her book.

In conclusion, Imogen Saunders’ book General Principles as a Source of International Law delineates an alternative, distinctive and critical account of the evolution, formation, and function of General Principles, based on comprehensive analysis and original methodology.

-

Nicole Rinaldi de Barcellos holds a PhD in International Law from the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, in Brazil (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul/UFRGS)