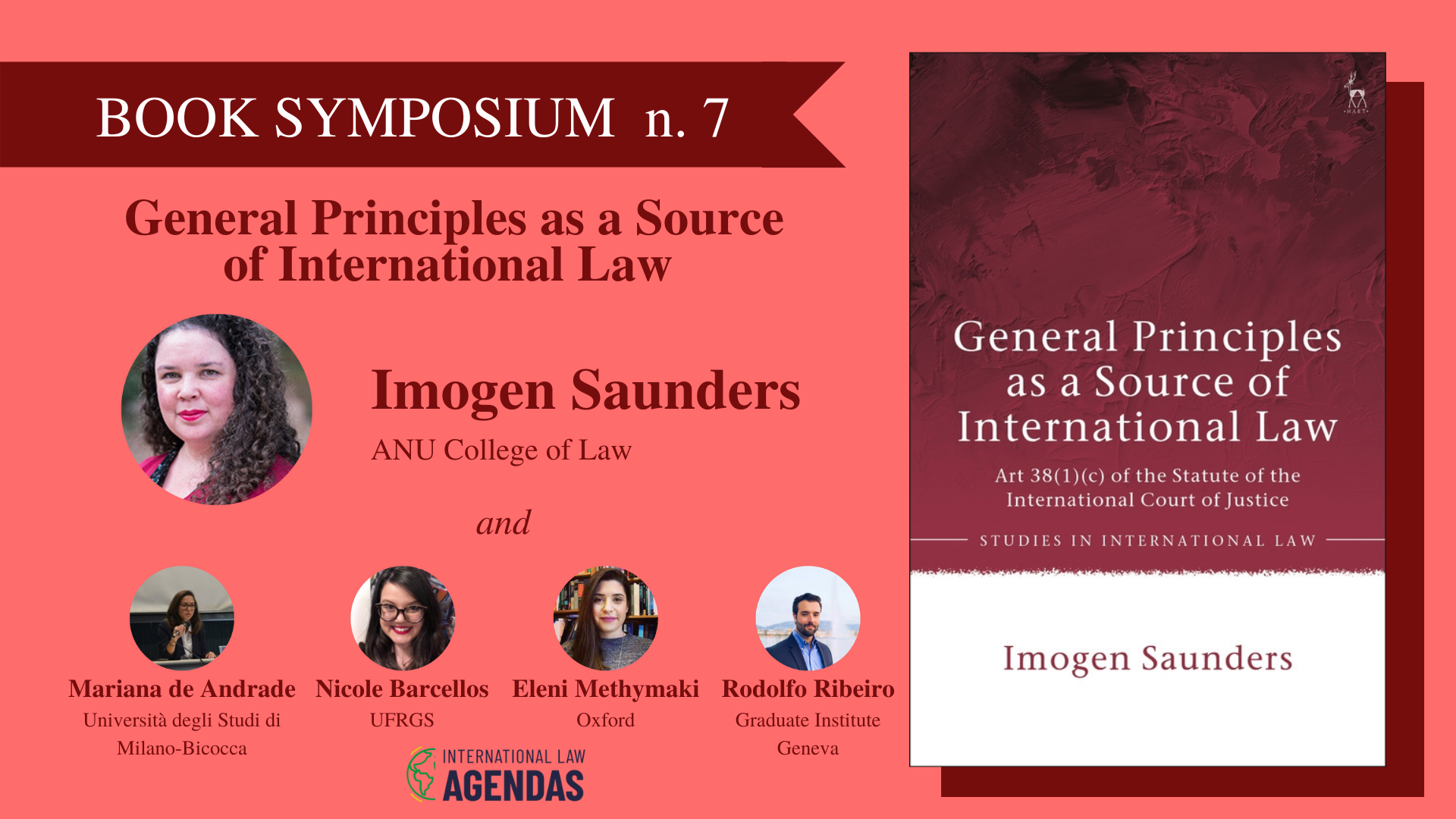

First, a heartfelt thank you to Mariana Clara de Andrade, Nicole Rinaldi de Barcellos, Eleni Methymaki and Rodolfo Ribeiro for their generous and thoughtful engagement with my book. Thank you also to the editors of International Law Agendas for arranging this review symposium.

I started exploring Article 38(1)(c) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice when I was still an undergraduate. The source accompanied me through an honours thesis, a PhD, and finally resulted in this monograph. What started as a quite black letter, doctrinal and case-based exploration of the source turned into something quite different by the end. Although the case analysis remains (4 chapters spanning 61 ICJ cases, 23 PCIJ cases and an overview of cases from the ICTY, the ICTR, the ICC, the World Trade Organisation DSB, GATT and ICSID tribunals/panels, the ITLOS and selected regional courts), the heart of the book has shifted. I describe my project as a quest – at first, it was simply to answer the question of what a General Principle is, and how it is found. One of my colleagues asked of another colleague at a book launch a question that has stuck with me: ‘who were you so annoyed at that you wrote this book?’. Perhaps not all academics are driven by annoyance, but for me it can be a motivating factor. My initial annoyance was driven by what I saw as an irritating fuzziness in the way the source was treated, a tendency of some commentators to make assertions without providing evidence and grouping disparate concepts together with seemingly little distinction drawn or recognised. In this way, the book is indeed as Eleni Methymaki states ‘…a plea for precision and clarity in our own research work’.

The search for this clarity led me to the development of a tetrahedral framework – beautifully described by Rodolfo Ribeiro as ‘…like light passing through a prism, Saunders’ tetrahedron purports to break down general principles of law in four different elements…’ – function, methodology, type and jurisprudential legitimacy. I then applied this framework to the cases, breaking down each use (and purported use) of General Principles to see what it could reveal about each aspect. By the end however, I realised the quest couldn’t be met by the cases alone. An understanding of General Principles requires exploring its context and a critical evaluation of the role that history, geography and identity all play in providing this context. Indeed, such context can explain in some ways the fuzziness – and opens exciting avenues for the future use of the source. I am pleased that the reviews in the symposium have focussed on these aspects, because I think they are both the key to building a model of General Principles, and the most interesting part of the book.

History

Although the concepts of history, geography and identity are inextricably linked both when considering general international law and General Principles, I will nonetheless try and address each separately. A usual approach to the history of General Principles is to trace the development of the source back through time – most often starting with the work of the Advisory Committee of Jurists. In fact, the development of the source can be traced back to at least 1875, with the Institut de Droit International’s Arbitral Procedural Regulations and the accompanying commentary of Levin Goldschmidt. This analysis – which I undertake in the book – is important, as it provides a basis for some of the later linguistic analysis of terms such as ‘rules’ and ‘principles’, as well as providing a clear positioning of General Principles as an alternative source to one based on unfettered judicial discretion. But it is ultimately a narrow one, as it by itself it fails to account for the deeply troublesome use of ‘civilized’ in the source, or the fact that General Principles have, for most of their life, been a ‘Concert of Europe’ (to use the words of Judge Ammoun).

Geography

This insight then leads to a discussion of the geography of General Principles. I argue that General Principles have not been, but must be, treated truly globally. Not many commentators would dispute my first assertion, but surprisingly there are still some scholars today who believe a consideration of (mostly European) civil and common legal systems can be a legitimate and valid shorthand for consideration of global legal systems. None of the four reviewers in this symposium fall into this category, and I am delighted by Mariana Clara de Andrade’s response to my appeal to universalism in her decision to write her review in Portuguese. A critical approach to General Principles requires consideration beyond the thin veneer of imposed legal systems, and must include religious and chthonic legal systems. Although I argue that the burden of this not inconsiderable comparative work is not nearly as onerous as in the past, due to technological change, de Andrade’s criticism that this itself is an English language-centric position is well-made. Nonetheless, it is important, as Nicole Rinaldi de Barcellos states, for accounts of General Principles to respond ‘to the need for democratization of the sources of international law and taking into account the rich diversity of cultures and legal traditions involved.’ This is where I hope my book leads in part – that those better positioned than I can take up the cause of championing truly global General Principles.

Identity

The main identity paradigm I discuss in my book is geographic based: national identity of judges and of commentators impacts on understandings of General Principles. The national identity of judges has long been linked to Article 38(1)(c), with Article 9 of the Statute of the ICJ seen as a way of ensuring representation in the ‘civilized nations’ considered. In practice this has largely not happened. Most comparative studies used by international courts have been very limited. Moreover, as I explore in the book, the actual representation of judges in international courts and tribunals is not as diverse as one might hope. National identity of commentators is also important to understanding General Principles, with clear divides along different national international law schools of thoughts. As Anthea Roberts brought to the fore, international law in many ways is not really international at all: we are a divided academy, and this division plays out in works on General Principles. This diversity is not necessarily a bad thing: but it does loop me around to where I started. There is a need for precision in how we talk about General Principles, and an unpacking of assumptions which may not be universally held.

Future Directions

Ultimately, I discovered recognition of an inherent duality within General Principles was the key to developing a model that could sit comfortably with the historical development and use of the source, being judicially defensible, and also provide a way for General Principles to be used in the future. The push and pull between positivism and natural law, between rule and principle, between generality and specificity can all be encompassed in the model. Where to now is best left with the reviewers in this symposium, who all suggest exciting and valuable future directions centred around the unique ability of General Principles to engage outside the (Western) State dominant discourse of traditional international law. This includes looking to transnational regulatory processes (Ribeiro); creation of new areas of international law outside of state to state interactions (de Barcellos); engaging with legal systems left aside by traditional practice of international law (de Andrade) or a re-evaluation of how international law reacts with domestic law, and ‘which domestic laws and which domestic legal systems are viewed as producers, or co-producers, of international norms and which are permanently confined to the status of ‘fact’, only evaluated for compliance or non-compliance with international law.’ (Methymaki). All four would be welcome directions, and I hope my book provides some guidance for those wishing to undertake such work.

-

Dr Imogen Saunders is a leading international law researcher. Her work has been published in field leading journals such as the American Journal of International Law, the Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law and the Australian Yearbook of International Law. Her monograph on General Principles of Law as a source of international law (Article 38(1)(c) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice) is now out with Hart. Imogen is part of the three institution Backlashes Against International Law research collaberation. As well as the Backlash project, Imogen is currently working on projects on COVID-19 and international law and the history of women in international law. Imogen completed her undergraduate degrees in law and science at the University of Western Australia, and was awarded her PhD from the Australian National University in 2013. She teaches international law and international trade law in the LLB/JD and LLM programs. She is currently the Director of Teaching and Learning at the ANU College of Law.