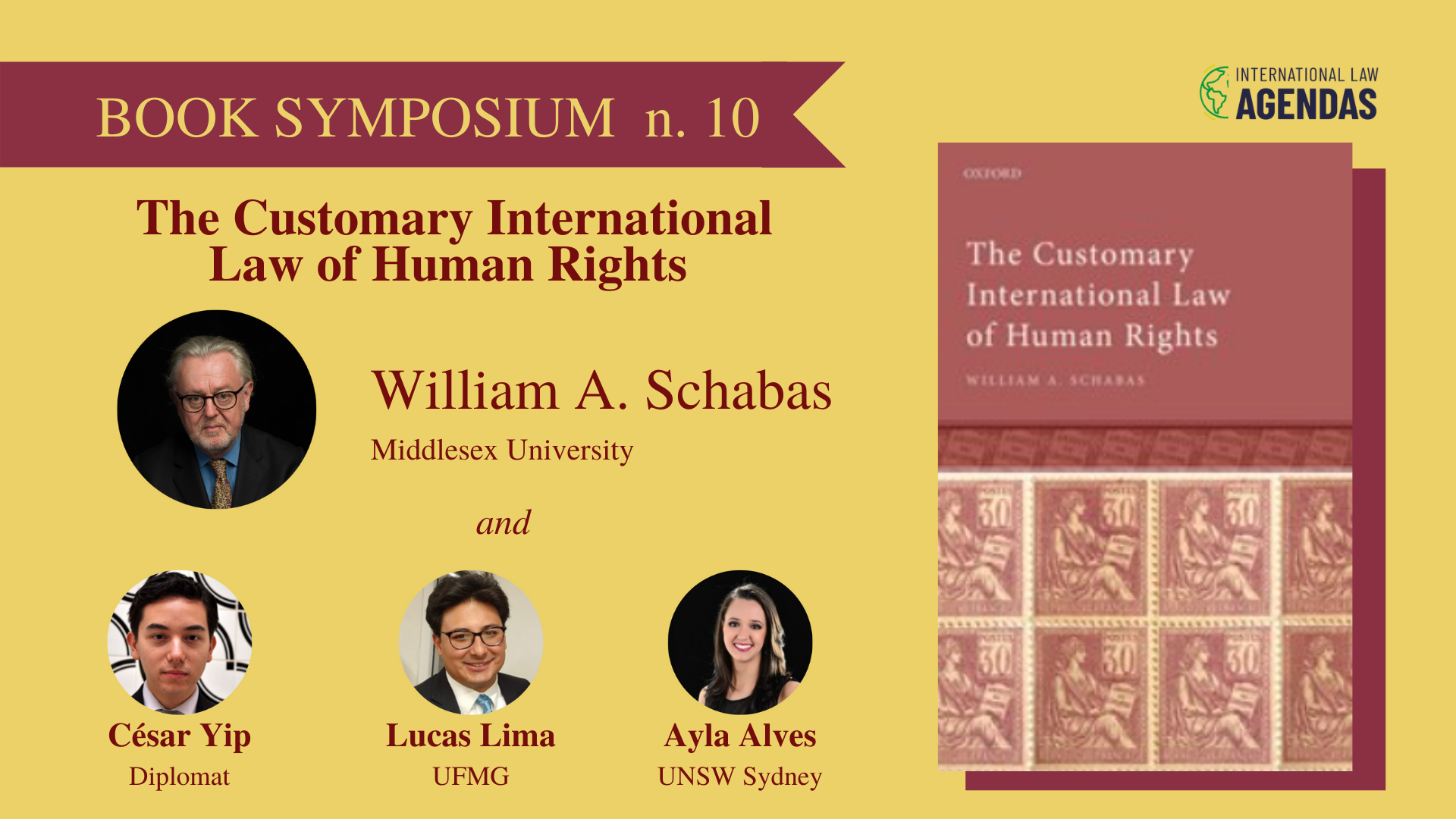

I am most grateful to Cesar Yip, to Ayla Do Vale Alves, and to Lucas Carlos Lima, all of them having taken the time to read my new book and to reflect on the issues with which it is concerned. Also, many thanks to Lucas Lixinski who is the originator of the project.

The book was published mid-way through 2021, at the height of the pandemic. It was many years in gestation but only when things shut down in early 2020 was I able to concentrate my energy and finish the study. My home in London is only a short tube ride from the British Library. It is only a bit further to the National Archives. Alas, these fabulous resources were inaccessible during the lockdown. Fortunately, virtually everything I needed to do my research on customary international law was available online.

But if the pandemic created the serene environment for research, it also had a negative effect, perhaps one that was compounded by Brexit. My publisher, Oxford University Press, had supply problems and the book was not easily available. Friends said they tried to order it on more than one occasion but without success. And this logistical obstacle’s effects also showed in my end of year royalty statement. Academic writers rarely rely upon royalties in order to pay the mortgage, but we very much like to see that many people are buying the book because that suggests they are engaging with our ideas. It also increases the hits on Google Scholar.

One of the reviewers, Cesar Yip, takes up the relationship between treaty law and customary law. I attached a lot of importance to treaties as evidence of customary law, to the extent that they are very widely ratified. I do not think I ever suggested that this factor is decisive but I certainly consider it to be important. Some academics like to play the role of Moses coming down from the mountain and pronounce certain rules to be customary in nature. This is far from my own approach. I think that the best one can do is to accumulate the evidence and then assess whether it is strong or weak, substantial or insignificant, compelling or unconvincing. In that context, a widely ratified treaty can play a huge role, especially combined with other forms of evidence.

One has to be careful here, because some treaties on important issues are not widely ratified or have big gaps in the pattern of ratifications, even though they seem to set out principles that are beyond question. This is particularly true of those with an international criminal law dimension, like the Genocide Convention, the Torture Convention and the Enforced Disappearance Convention. I think that the relatively lower rate of ratification for these treaties compared to instruments like the Convention on the Rights of the Child or the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women is explained by the obligations that are imposed rather than any objection to the norm itself.

Cesar Yip seems to appreciate my insistence upon the customary dimension of economic, social, and cultural rights, but he is also a bit disappointed because the discussion is a trifle summary. I think we probably agree that it would be desirable to provide specifics about the content of the right to health and medical care, for example. But can this be done when the formulations of the norms in positive law is also quite general? Perhaps this is particularly true in the area of economic, social, and cultural rights, because the obligations are mainly positive in nature and therefore involve difficult choices about the allocation of limited resources. We know that even when judges have the authority to rule in this area they often hesitate about being too prescriptive. I am thinking here about the great judgment of Albie Sachs at the South African constitutional court ruling on the right to housing in the Grootboom case.

The famous paragraph of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in Belgium v. Senegal on the customary nature of torture bears to be revisited. I am not sure if the Court did its homework properly. To support the recognition that it is a norm of customary law, the ICJ says the crime of torture ‘has been introduced into the domestic law of almost all States’. Do you really think the judges of the Court (or their assistants) actually checked this out? Only a few years before the judgment was issued, the Committee of Torture issued a General Comment with very detailed instruments about the importance of appropriate legislation to make torture punishable. Why would it have wasted its time if ‘almost all States’ had already done this? Complaints about inadequate codification of torture regularly appear in Concluding Observations of treaty bodies as well as in Recommendations during the Universal Periodic Review.

Lucas Carlos Lima is focussed on regional human rights norms. This is certainly a subject that could be developed in more detail than I did. Unfortunately, we still do not have the universal human rights court, so the only international courts we can consult are regional. But the problem with identifying regional norms by relying upon the case law of regional human rights courts is that they apply treaties rather than custom. The European Court of Human Rights frequently looks at customary international law, but on tangential issues like immunities rather than on the substance of human rights. Exceptionally, individual judges, like Judge Paolo Pinto de Albuquerque, venture into the customary law zone. but he is no longer on the Court and it does not seem that his shoes have yet been filled.

The Inter-American Court is as reticent about customary international law as the European Court. It likes to skip a level and go straight to jus cogens. Perhaps the thinking is that a court with jurisdiction based upon a treaty is not entitled to amplify its jurisdiction with reference to custom in the same area. There is some sense to that view. On the other hand, jus cogens is inescapable. The problem here is that the relationship between treaty law and jus cogens is about hierarchy. The Vienna Convention looks to jus cogens as a limitation upon the scope of treaties and that is obviously not what the Inter-American Court is trying to do.

Lucas Carlos Lima also addresses the issue of the two elements. For decades, those seeking to promote the customary law of human rights felt compelled to challenge the role of state practice. Then the International Law Commission said this was not a correct approach. I think my own approach has been misunderstood as one that supports the Commission’s conclusions. But all that I am saying is that there is no need to dwell upon opinio juris and downplay State practice because there is now, thanks to the Universal Periodic Review, abundant evidence of the latter.

Ayla do Vale Alves focusses on the role of customary law in the area of the rights of Indigenous peoples. Her comments go to an issue that I did not properly address, and that is very much the subject of the book that I am currently writing. Regardless of whether there is one element or two, both custom and treaty law are nothing more than two peas in the pod of public international law. Taken as a whole, this is a body of law that was created by and for European merchants and colonisers who considered that it applied only to ‘civilised peoples’. Their law was never meant to serve the ‘uncivilised’ who were viewed as objects rather than subjects of international law. However, for at least a century international law has been a battleground. Its norms can be used to advance the rights of Indigenous peoples, even if this was far from the minds of those who initially developed the field. Ayla and myself are probably on the same wavelength here.

Some of the comments spoke about new editions of my book. Of course I would hope that it will be revised and updated at some point. I am getting closer to the finish line of my own career, so I may never get to the second or the third edition. Perhaps one of you three will take over?

-

William A. Schabas OC MRIA Professor of international law School of Law | Middlesex University | London | United Kingdom